Last week, Ron Jaworski went on SportsCenter and talked about Michael Vick’s potential in 2012:

“Vick has shown he is capable of throwing the ball exceptionally well from the pocket,” said Jaworski. “His overall throwing skill set can be top five in the league. His objective in 2012 must be to play that way more often. It becomes an availability issue. You can’t be an elite NFL quarterback if you can’t be counted on every single week.

“I am really excited to see Michael Vick in 2012. A more disciplined player will result in fewer turnovers. I would not be surprised if we’re getting ready to see the best year of Vick’s ten-year career.”

While Jaws supposedly watched every 2011 snap of Vick, his conclusions seem half-baked, especially compared to Sheil Kapadia’s epic breakdown of Vick’s game for the Eagles Almanac (plug alert!). For example, Sheil noted all of Vick’s injuries came on hits in the pocket, not because he was running around. Availability seems to be less of an issue (an NFL team loses its starting QB, on average, for three games a season) than accuracy and decision-making.

Regardless, Jaws’ sentiments are those I think a lot of fans hold. Vick had an amazing season in 2010, then fell back to Earth in 2011. But, we are told, his first full offseason as the starter with Marty Mornhinweg and Andy Reid will push him back to the top. It’s not a crazy opinion, but it is an optimistic outlook, and one that I’m not sure there’s any more evidence for than that Vick has already peaked, and he’ll never again reach that height.

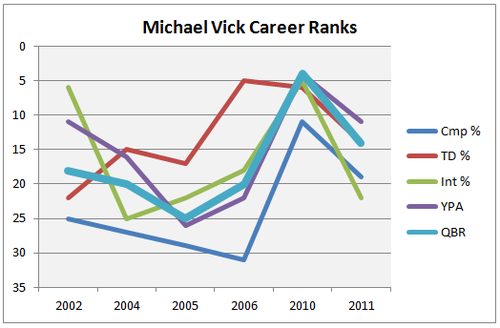

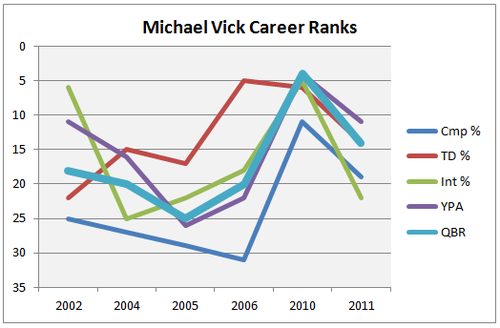

In the spirit of a series of posts I did about Donovan McNabb two years ago (yeesh, that long ago?), I put together a new graph showing where Vick ranked on key statistics, during the years he was the main starter. By focusing on the rankings, rather than the stats themselves, we can see how well Vick has done compared to his peers — since the last ten years has resulted in a better passing environment pretty much across the board. QB Rating is slightly bolded because it’s more of an aggregate indicator than a separate statistic.

Obviously, Vick’s passing career has been less than stellar overall. Through 2006, he was below average across the board, and especially terrible in completion percentage. He went on his two year hiatus, came back as a wildcat threat in 2009, and resurrected triumphantly in 2010.

The question of “what’s next?” remains, though. There was a big drop off from 2010 to 2011, approximately from Aaron Rodgers-level to Jay Cutler-level. Was that a temporary bump in the road, soon to be righted after an offseason of hard work? That’s certainly the conventional wisdom right now.

The other answer, while not necessarily disastrous, is significantly less Super Bowl-worthy. That possibility suggests that Vick simply regressed to his career mean. His numbers were still up from 2006, but one might attribute that to slightly improved play and a much better supporting cast. Vick never had DeSean Jackson, Jeremy Maclin, Brent Celek, and LeSean McCoy in Atlanta.

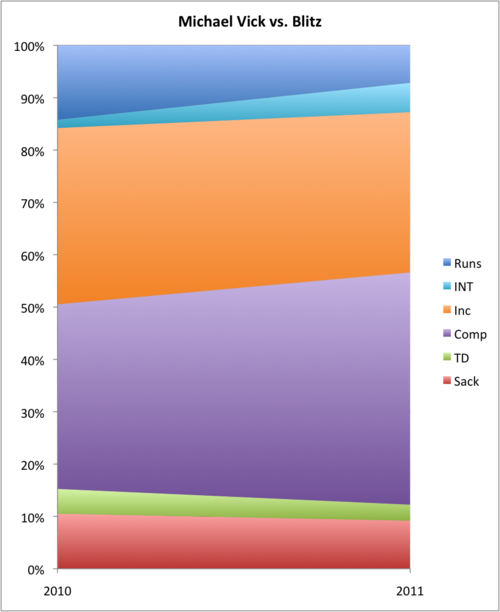

Ultimately, there’s no such thing as a prediction engine for player performance. Vick may really benefit from these months of personal tutoring, allowing him to overcome the blitz-happy adjustments many teams made against him last year. Or, at 32 years old, it may be too late for him to completely change his ways. Jaws’ statement about Vick’s talent and potential are the same things people have been saying about him for the last decade.

One’s personal expectation probably has a lot to do with your thoughts on Mornhinweg and Reid’s mentor skills. In my experience, you doubt their abilities to coach and gameplan at your own risk. But I also wonder how much this ballyhooed “first full offseason as a starter” will really make a difference. Vick has been playing at a more mediocre rate since the end of the 2010 season, and we’re supposed to believe the three of them haven’t had time until this offseason to go over that?

For now, among the cautiously optimistic analysts, consider me more cautious than than optimistic.

Photo from Getty.

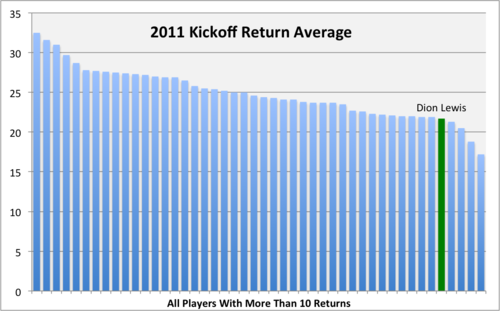

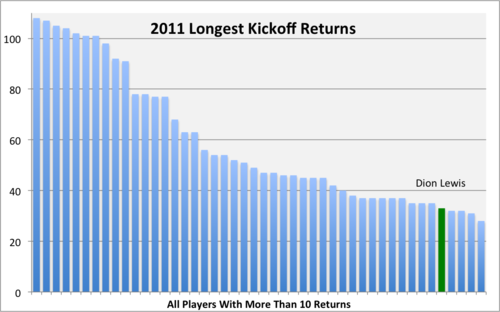

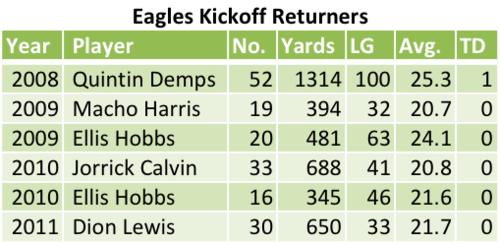

It’s worth pointing out that this isn’t a problem solely related to the rookie from Pitt. Lewis is only the latest in a string of poor kick returners, who you can see at right. He was actually better than Jorrick Calvin. Quintin Demps, back in 2008, was the last above-average returner the Eagles employed. It would be nice to see the Eagles try to correct that in 2012, although I won’t be holding my breath.

It’s worth pointing out that this isn’t a problem solely related to the rookie from Pitt. Lewis is only the latest in a string of poor kick returners, who you can see at right. He was actually better than Jorrick Calvin. Quintin Demps, back in 2008, was the last above-average returner the Eagles employed. It would be nice to see the Eagles try to correct that in 2012, although I won’t be holding my breath.

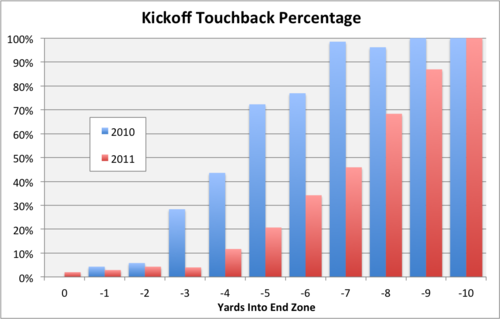

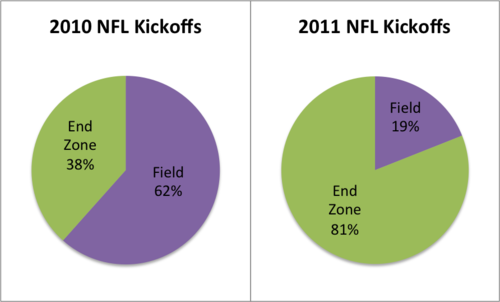

Just how much did those extra five yards help the kickers? Check out the graphs at right.

Just how much did those extra five yards help the kickers? Check out the graphs at right.