Last March, Jeff Lurie told reporters he was was tired of waiting for the Eagles to be great. He’d seen sustained success, he’d been to a Super Bowl, and he’d watched his franchise post a solid 20-13 record (including a playoff loss) over the prior two seasons. It wasn’t enough.

“I’ve lived through a lot of division championships, a lot of playoff appearances, a lot of final four appearances, but our goal is we want to deliver a Super Bowl,” he said at the time. “And sometimes maybe I’m influenced by the notion of it’s very difficult to get from good to great, and you’ve got to take some serious looks at yourself when you want to try to make that step. It’s a gamble to go from good to great because you can go from good to mediocre with changes, but I decided it was important enough…”

On Wednesday, after firing Chip Kelly before the final game of the season, Lurie didn’t walk away from his words earlier in the year.

“I said, with Chip’s vision, it was an opportunity that he wanted to lead the way, to try to go from good to great,” he said. “In fact, I remember saying to all of you, there’s dangers in that, in terms of having two 10-6 seasons in a row, and when making significant changes, you can easily achieve mediocrity. I think it would be a shame not to try, but… that is the danger when you take a risk.”

I hope Lurie learned more than that, because his "strategy" was little more than a desperate hope. He handed over all power to Kelly, a moderately successful coach with zero experience running the intricacies of a NFL organization.

The road to the Super Bowl is not paved with such gambles, with an outsider making a bunch of questionable bets that luckily pay off. You don’t win by cutting talent and building #culture. You don’t win with a rigid set of measurables that dictate player acquisition. You don’t win by ignoring critical positions and spending excessive guaranteed money on less important ones. You don’t win by overpaying for a subpar quarterback coming off two major knee injuries, or turning over half the roster in one offseason. That’s how you end up 7-9 in one of the worst divisions ever.

There are no shortcuts.

Remember Andy Reid’s binder? Reid came to Philadelphia with a detailed multi-year plan of how to build an organization. He arrived in 1999, overhauled the roster, brought in an impressive group of experienced coaches (including 6 eventual head coaches), drafted a quarterback in the first round, and went 5-11. In 2000 the team and young quarterback improved, overachieving to reach the playoffs. By 2001 they were one of the best teams in the conference. In 2002 and 2003 they missed the Super Bowl by inches. In 2004 they came minutes away from the trophy itself.

Lurie said he doesn’t want the middle steps, he just wants the Super Bowl, and he was willing to gamble to get there. But those middle steps are important. That’s how you build a champion—not overnight, but consistently, step by step.

The best teams in the NFL have the best talent. The best teams in the NFL have a top quarterback they drafted and groomed. The best teams in the NFL have smart, experienced coaches who adjust their schemes to the players they have. The best teams in the NFL have a front office structure that empowers multiple voices and balances scouting with analytics and financial understanding.

Going into 2016, the Eagles need to avoid the quick fix, or the allure of competing for the playoffs in year one of a new regime. That won't set the team up for long term success. (Plus, they'll likely be in the running anyway unless the putrid NFC East changes significantly in a year.)

The blueprint needs to be for a Super Bowl contender in 2018. Let's lay out what that looks like...

Front Office: Howie Roseman has a mixed reputation among fans and league sources, but he can succeed in the Joe Banner role. He has experience on the personnel side to pair with a firm grasp of the league's economics. Roseman does need to find a qualified general manager-type to run player personnel, someone less washed-up than Tom Donahoe, with more experience than Ed Marynowitz, who's not obvious idiot Ryan Grigson.

Coaching: A NFL team is a crazy thing to manage, and any head coach needs to be able to bring in the right people and command respect across the organization. He doesn't have to be a brilliant innovator on the cutting edge, but he does need to be flexible enough to adapt his schemes and techniques to get the most out of his players in each situation. The single most important skill set within that is the ability to find and develop a franchise quarterback, which is what makes a candidate like Adam Gase so attractive.

Quarterback: You cannot be a consistent Super Bowl contender until you have a quarterback. As such, you should exhaust every possible avenue to get one, especially the draft. I stand by my recipe for QB hunting laid out four years ago, on the eve of Andy Reid's firing:

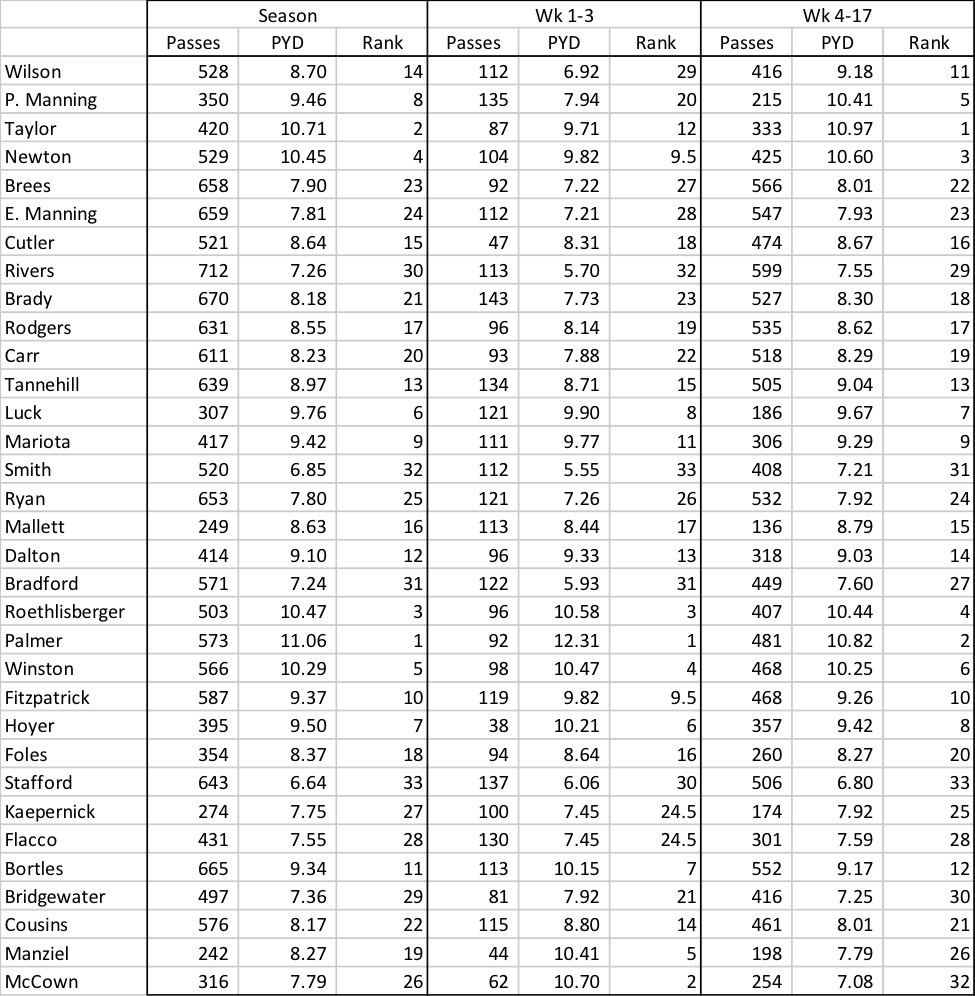

Draft a quarterback early and late. Sign somebody in free agency. Trade for a promising backup. Rinse and repeat. You're never going to be able to compete for the Super Bowl until you find your one franchise guy. Might as well cycle through as many potentials as you can until you do. The financial cost of doing so is less than the opportunity cost of sitting pat with one player, [Bradford], who is statistically unlikely to ever become an elite quarterback.

In the Eagles' case, that means avoiding any multi-year guarantee to a still-unproven quantity like Sam Bradford, and perhaps letting him go entirely depending on the cost.

Roster Building: Outside of quarterback, which takes priority over everything else, the offensive line is next on the list of must-haves. Though I don't know many of the names, Jimmy Kempski's mock draft would thrill me based on the selection of two quarterbacks and three offensive linemen. Lane Johnson and Jason Kelce are the only long term building blocks you can count on there. Meanwhile, don't waste resources on the rest of the offensive skill positions, none of which will matter much until the offensive line and quarterback are fixed.

The Eagles defense needs more talent across the board, but it also likely needs a scheme that better takes advantage of the players in house. Kelly wanted a two-gapping 3-4 system, but it would be nice to see what Fletcher Cox and company could do in a one-gapping 4-3 instead.

Overall: Both the organization and its fans need patience. We were spoiled by Chip's quick turnaround, but where did that leave us? Let's plan for sustainability.

Read more: How The NFL Chewed Chip Kelly Up And Spit Him Back Out