The following is a guest post by @sunset_shazz.

This is a wonderful time to be an Eagles fan. Jim Schwartz’s Attack Nine defense is rapidly exorcizing the ghost of Juan Castillo. Doug Pederson has rejuvenated an offense that had become stale and predictable under Chip Kelly. And, of course, rookie quarterback Carson Wentz is turning heads across the league, not to mention in the oval office.

Eagles fans, unexpectedly blessed with success, look to the poet Browning to give voice to their collective sentiment:

The lark's on the wing;

The snail's on the thorn:

God's in His heaven—

All's right with the world!

But wait. From his perch at the indispensable Football Outsiders, Scott Kacsmar has some discomfiting news: both Wentz and Cowboys rookie QB Dak Prescott are mere dink and dunkers, with lower than average air yards per attempt (defined as the average distance a football is thrown beyond the line of scrimmage). A low score on this metric is undesirable, in Kacsmar’s view.

The inimitable Jimmy Kempski responded to Kacsmar’s initial claim with a sardonic video rewind post, prompting Kacsmar, in an entertainingly vitriolic rant, to frame this argument as a contest between enlightened, statistically rigorous analysts on one side and straw-manning “numbers are for nerds” egg avatars on the other.

I don’t believe that view is correct.

A statistic that both correlates with winning and correlates with itself would be a reliable predictor of future wins.

First, you want your in-sample measure to have some predictive power in estimating out-of-sample future wins, because, hello, you play to win the game. Second, you want a metric to have some degree of statistical persistence over time, in order to be confident you are measuring a signal (in this case, an attribute of quality quarterbacking) rather than mere noise.

Regarding the latter, Kacsmar notes that in 2015, the correlation between air yards in the first three weeks of the year and the air yards for the entire season was 0.80. Well, that doesn’t seem quite fair, does it? After all, what we really care about is the correlation between the first 3 weeks of the season and the ensuing 14 weeks. Using his dataset, and using the Spearman rank correlation estimator rather than a standard Pearson estimator, which in this case would be considered less robust, I found that the correlation between the first 3 weeks and ensuing 14 weeks last year was 0.60. That’s pretty good, as far as football statistics go. However, do note that within a season a number of other factors surrounding the quarterback are, for the most part, held relatively constant: coaching scheme, strength of running game, defensive strength, etc.

When Chase Stuart examined the persistence of the Air Yards metric from year to year, he found that between 2006 and 2012 for 100 qualifying QBs the correlation between Year N and Year N+1 for Air Yards was 0.34. Both completion percentage and yards/attempt were “stickier” with N to N+1 correlations of 0.51.

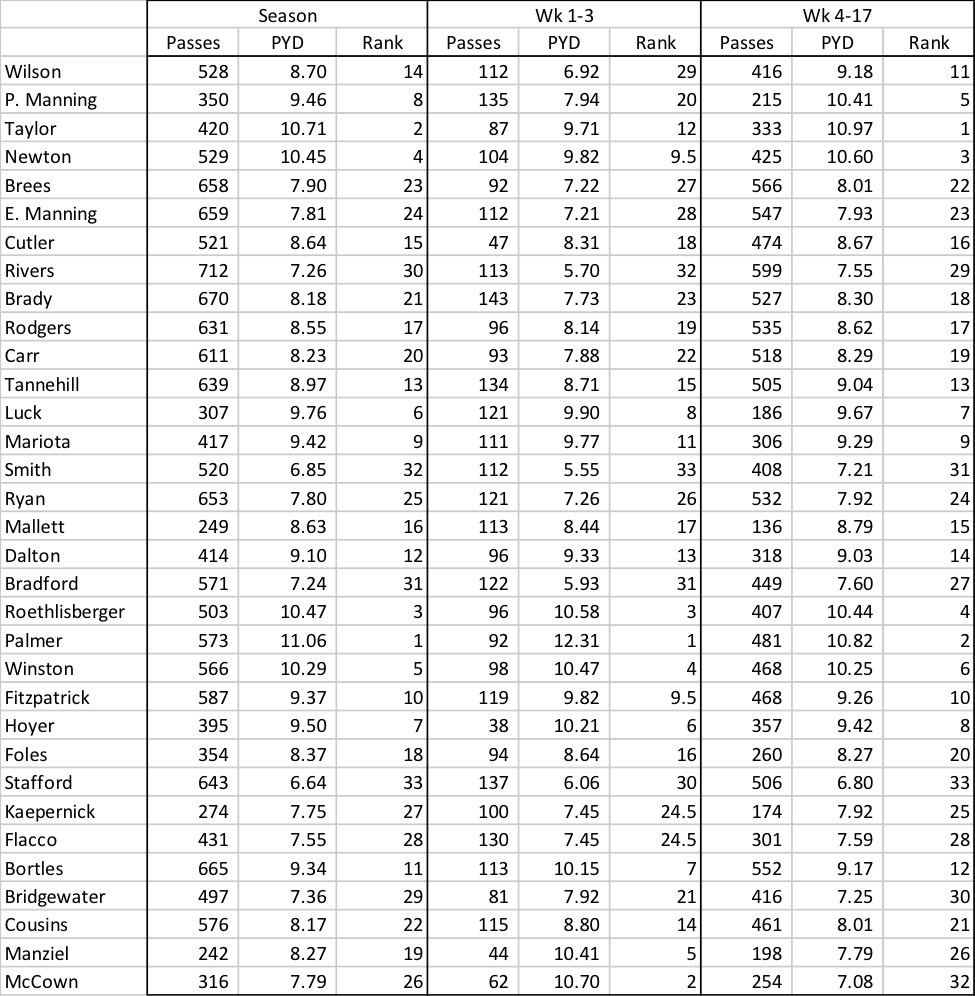

Kacsmar, in his FO piece, assembles a smaller dataset (than Stuart, above) which he judges to be salient:

I gathered that yearly data on 21 quarterbacks with at least four years of starting experience, all of whom are still active starters this year except for the retired Peyton Manning. The following table shows their average air yards by year for the period of 2006 to 2015.

The first rule of Analytics Club is to plot your data, so I plotted Kacsmar’s data into a time series chart, in order to visualize the range and variability of the attribute, segregated by quarterback, over time:

Taking Kacsmar’s dataset (which, it is important to note, uses 21 quarterbacks who have experienced some career longevity rather than Stuart’s more comprehensive analysis of 100 QBs), and running a similar autocorrelative N to N+1 analysis, I found that the year-to-year correlation was 0.40. My friend, real-life data scientist Dr. Sean J. Taylor, was generous enough to both replicate my work and provide me with a scatterplot, complete with line of best fit and confidence interval shading:

Chart courtesy Sean J. Taylor

The autocorrelation statistic, the scatterplot and time series visuals each show the same thing: we are measuring mostly noise, with a faintly detectable QB signal. The attributes I mentioned before—scheme, effectiveness of the running game, defensive efficiency which affects game script—are all likely to change the calculus of decision-making with regard to throwing shallow or deep.

In fact, Kacsmar himself gives us a good reason to doubt the validity of Air Yards in capturing an attribute of QB quality: it doesn’t improve as a player gains more experience. Quarterbacks, like all athletes, typically experience an age curve, reflecting both athletic maturation and decline, as well as the steep learning curve imposed by formidable NFL defenses. Chase Stuart has shown that the age curve for NFL quarterbacks is pronounced. The absence of an “age/experience curve” for Air Yards is yet another red flag.

Air Yards doesn’t appear to measure a persistent quarterback attribute over time, particularly when compared with a conventional statistic such as completion percentage or advanced statistics such as Adjusted Net Yards / Attempt (ANY/A, for which Danny Tuccitto brilliantly used confirmatory factor analysis to verify its validity) or Defensive Yards Above Replacement (DYAR, rigorously developed and tested by Aaron Schatz).

But does it predict wins?

My general model of the production function of football is as follows: runs and passes are inputs; completions and first downs are intermediate goods; points are outputs. Success rate metrics such as Defensive-Adjusted Value Over Average (DVOA), DYAR, and ANY/A are all measures of intermediate goods which are of interest to the analyst because they tend to reliably convert to points. And as Chip reminds us, if you (f__king) score points you are more likely to win.

Chart courtesy Sean J. Taylor

The scatterplot above shows the relationship between a QB’s average air yards over a season and the points scored by his team over that season. There is no statistically significant relationship between the two measures. Contrast this with ANY/A, which correlates 0.55 with wins. Or DYAR & DVOA, whose parameters were specified in order to predict future wins.

Kacsmar has been careful to note that he isn’t an advocate of maximizing Air Yards; he thinks middle is best. He elaborates in his FO piece:

Generally, air yards are a stat where you don't want to rank at the bottom, because that is where many ineffective passers dwell, including Blaine Gabbert. That preference for short throws often extends to crucial downs, which is why these quarterbacks tend to do poorly in ALEX and attacking the sticks. However, it is not preferable to rank at the very top in air yards either, because that is how "screw it, I'm going deep" players such as Michael Vick, Tim Tebow, Vince Young and Rex Grossman have earned their reputation as inefficient passers.

His claim, if I have understood it correctly, is that quarterbacks at the tails of the distribution are less likely to be successful in future. Our scatterplot above doesn’t show any relationship between the middle of the distribution and success, measured by points scored. But could Kacsmar’s anecdotal observation that “middle is best” be a mere artifact of sampling? If successful quarterbacks have longer careers, the law of large numbers dictates that they will, by mere virtue of larger samples, be less prone to the extremes in Air Yards. Taking a separate dataset evaluating quarterback air yards between 1992 and 2012, and plotting those against passes thrown, one arrives at the following:

You can see that the more passes a given quarterback throws, the less variance he exhibits with respect to his peer cohort. This needs to be examined further, in my view. I admit that I am not familiar with the nuances surrounding various measures of air yards (various observers have different estimates), but a longer, broader dataset would be desirable to plot air yards versus attempts. We don’t want to fall prey to the famous Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation misstep where it was initially claimed that small schools are consistently among the best performing schools, when it was merely the case that small schools experience more variance than larger schools, and therefore disproportionately comprise the tails of the distribution.

Here is the plot of the fourth-grade math scores versus number of students in the school:

The prior two sections showed that Air Yards as a measure is neither statistically persistent nor predictive of success, in terms of points scored. I did mention some alternative, robust metrics, two of which are generated by Football Outsiders. As of Week 3, FO has not applied opponent adjustments to their measures. On a raw Value Over Average and Yards Above Replacement measure, these young QBs have performed in the top quartile over the first 3 games.

Looking merely in the rearview mirror, without making any judgments about the future, they appear to have performed well.

Another measure I have mentioned, Adjusted Net Yards / Attempt (the “adjustment” gives a bonus for touchdowns and a penalty for interceptions, and the “net” deducts sack yards) is a persistent, predictive measure. With a hat tip to the excellent Derek Sarley, I prefer to plot this against completion %, to show both efficiency and consistency of per-play execution (weeks 1-3, minimum 46 attempts):

Once again, the rookies have played impressively: Wentz and Prescott are in the top quartile (4th and 8th, respectively) in ANY/A and the 2nd quartile (13th and 10th, respectively) in completion %.

As Bill Barnwell has noted, the statistics from 3 games tell us very little about how a QB will play in the future. A very small sample size disadvantages a purely statistical analysis; the comparative advantage shifts towards the film analyst. Ideally, one would combine both, but in this case, the stats aren’t meaningfully more robust than mere anecdotes. This is why I disagree with Kacsmar’s adversarial Michael Lewis-style “stats versus scouts” framing; the NFL stats on these two rookies don’t really tell you anything dispositive yet. From a purely Bayesian perspective, the eye test is just as likely as a mere three weeks of quantitative data to meaningfully update one’s priors. I have not yet enjoyed the privilege of watching Prescott, but I’ve seen every Wentz throw; moreover, I’ve seen astute film analysts such as Greg Cosell, Fran Duffy, Jimmy Kempski and Ryan from ChipWagon break his film down. Lastly, as Brent from EaglesRewind notes, one’s priors should be heavily influenced by draft position, which was the NFL auction market’s initial “revealed preference” view of value.

As for me, I’m on the Wentz Wagon. Dan McQuade reasons persuasively that Eagles fans should enjoy this run, because life is fleeting. Memento mori, football fans.

TL;DR:

- The early results from the credible advanced statistics, meaning those that tend to be both persistent and predictive, are that Wentz and Prescott have played well in their first three games.

- Looking at the numbers alone, a three game stretch is insufficient to give us high confidence that such success will continue in future.

- The Air Yards statistic is neither persistent nor predictive, and reflects the aesthetic tastes of one particular writer, rather than a desirable quarterback attribute.

Thanks to Sean J. Taylor for his methodological insight and scatterplot work. Any errors are mine alone.

@sunset_shazz is a Philadelphia Eagles fan who lives in Marin County, California. He previously wrote about Chip Kelly's Oregon bias and other topics, and contributed to the 2015 Eagles Almanac.