The following is a guest post by @sunset_shazz.

As the inimitable Jimmy Kempski recently explained, the Eagles’ defensive game plan is rather simple:

- Stop the run.

- Make the opposing offense one-dimensional.

- Get after the quarterback.

Indeed, Eagles opponents do appear to give up on the run – this year the defense has faced the fewest rushing attempts per game. One caveat: they also have the second-highest point-differential. As everyone knows, you face fewer run attempts when holding a lead.

Are the Eagles’ opponents giving up on the run because they’ve fallen behind? Or are the Eagles facing fewer rush attempts due to their stout run defense, irrespective of the scoreboard?

I examined Game Script data compiled by Chase Stuart. Game Script is basically the average score margin over a total game. As a stylized example, let’s say Team A returns the opening kickoff for a touchdown, kicks the extra point, then neither team scores for the rest of the game. Team A’s Game Script in this simplified example would be +7 (the average lead held the entire game); Team B’s Game Script would be -7. A higher game script is often associated with more rushing by the team who’s leading (because you run when you win, not win when you run) and more passing by the opposing team (which has a negative game script).

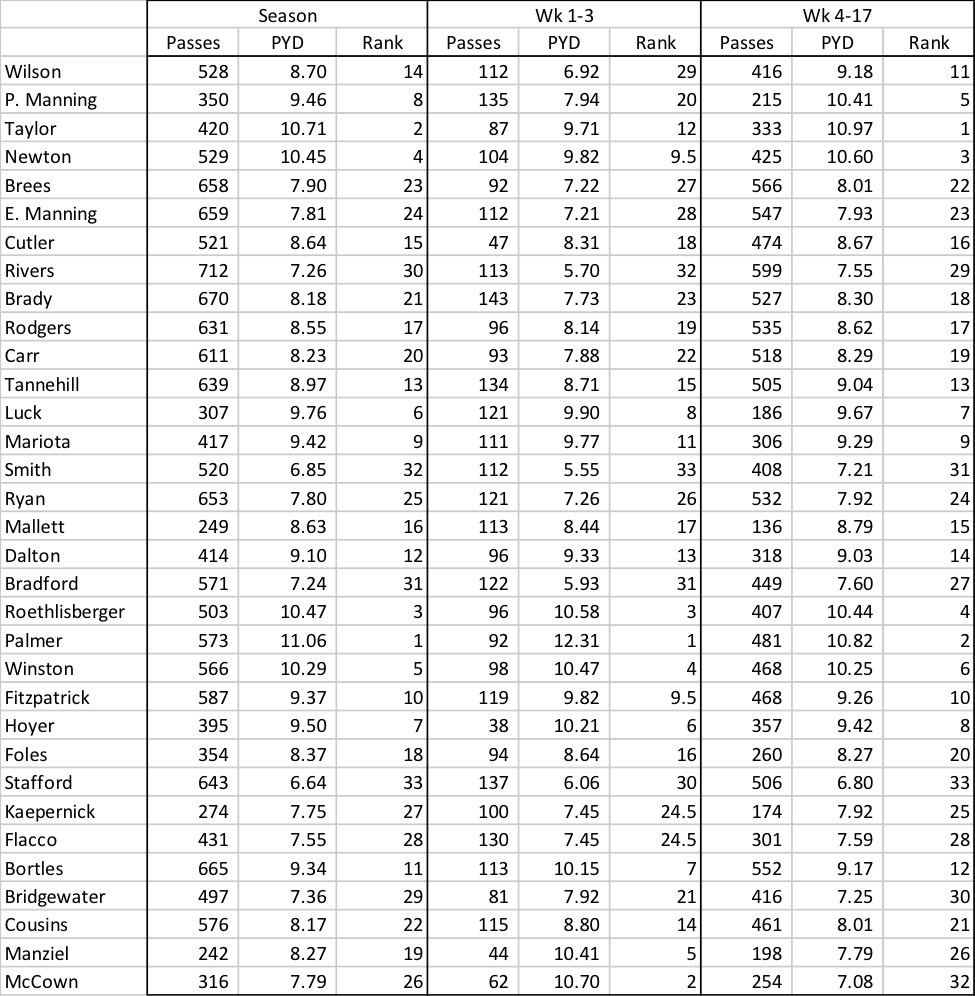

The plot below shows each team’s average Game Script on the X-axis and average Pass/Run Ratio on the Y axis (all data through weeks 1-10). The regression line represents the expected Pass/Run Ratio, given Game Script, computed from the 146 games that were played through week nine. [1] A team that is toward the right (LAR, PHI) has enjoyed a higher average lead, and a team toward the top (SFO) has a higher pass/run ratio.

By comparing each team’s pass-run ratio to what one would theoretically expect given game situation (denoted by the regression line above), one may construct a “Pass Heavy Index”:

This year, Bill Belichick has been 10.9% more likely to call a pass, given game situation, than average. With Mitchell Trubisky behind center, John Fox is 15.5% less likely to call a pass, given game situation, than average. Despite almost being run out of town after a week 2 game in which his Pass Heavy Index was +27%, Pederson is basically in the middle of the pack.

What about the defense? One may similarly plot each team’s opponent’s average pass/run ratio against the opponent’s average game script:

Did you notice the outlier on the upper left? One may also compute each team’s opponents’ Pass Heavy Index:

The table above shows that Eagles opponents are not only passing more than any other team’s opponents (70.1% of the time), but that they are the most pass heavy adjusted for game situation. The evidence supports Kempski’s thesis: Eagles opponents this year have become one dimensional. One way to look at it is that opponents have a healthy respect for the Birds’ run defense. Another way to view it: they think they can attack the secondary. Somebody please inform the Green Goblin that he’s being disrespected.

Stick Figure GIF reprinted with permission, courtesy Jimmy Kempski

Alternatively, perhaps this is an artifact of sampling bias – maybe the Eagles just happen to have faced teams who pass a lot (like Arizona).

Looking at it game-by-game, 6 out of 9 teams the Eagles played chose to pass more than they typically do, adjusted for game situation. There were three exceptions: the Cardinals 76.7% pass ratio, though 8.3% higher than expected, was a tad (0.5%) less pass heavy than Bruce Arians’ typical game; this was due to an extreme game script driven by a three touchdown first quarter by Carson Wentz. In the most recent two weeks, the Niners and Broncos both continued to run more than would be expected, despite falling behind by two scores in game script. Could this portend a change in opponent strategy, perhaps due to the absence of LB Jordan Hicks, whose season ended in the first series of Week 7? Or was this merely due to the injury to Joe Staley for the Niners and the move to Brock Osweiler for the Broncos? The next few weeks should be interesting.

The analysis presented above demonstrates that Eagles opponents are 10% less likely to run the ball than average, given the game situation. If opponents indeed are choosing to attack the Eagles’ passing defense, they are picking a different, though still potent, poison. The Eagles passing defense is ranked 7th in ANY/A allowed, and ranked 8th in defensive passing DVOA.

Interestingly, the Rams’ and Jaguars’ average lead has been similar to the Eagles’, though their opponents are running more than typical, given such a deficit. Those teams are ranked 2nd and 1st against the pass, respectively, in DVOA, and are ranked 15th and 30th against the run. Though opponents of each team are falling behind during games at a similar rate, they are choosing to attack the Eagles differently, given the relative strengths of their defensive units.

Thanks to Eagles fan Noah Becker and MoK Editor-in-Chief Brian Solomon for discussion leading to this post.

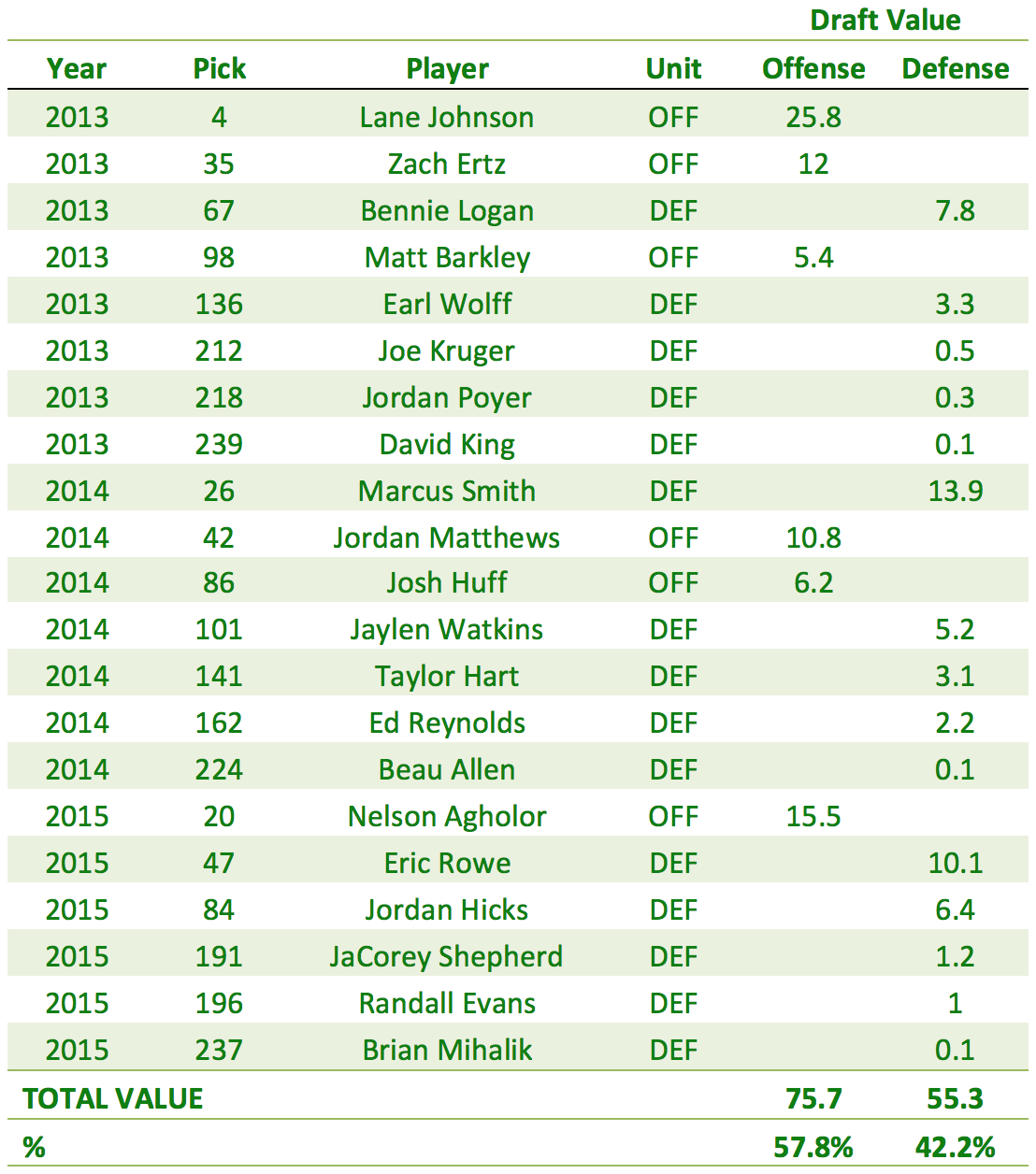

[1] The Y-intercept indicates the neutral pass/run ratio, 57.8%, which also mathematically corresponds to the league average pass-run ratio.