The following is a post by @sunset_shazz.

The National Football League has, over time, become a passing league. The best, most analytically sophisticated teams build around the passing game. In 2018, the final four teams in the NFC and AFC Championship games enjoyed the top 4 passing offenses, in terms of efficiency. In 2019, run-first teams are typically built by dinosaurs who can barely dress themselves.

The Philadelphia Eagles have made forward-thinking analytics a centerpiece of their strategy, and their fearless head coach is a protégé of one of the game’s great passing innovators; surely they are a pass-friendly offense?

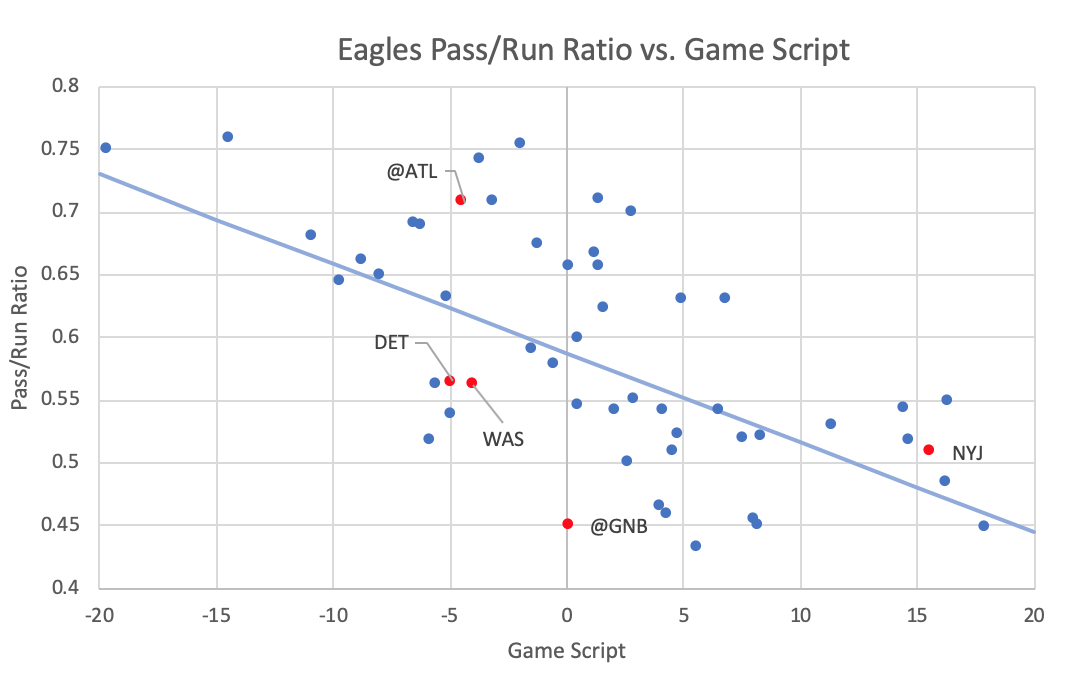

As I’ve noted before, any discussion of pass/run ratios must acknowledge the importance of game script, which is the time-weighted score differential transpiring over the course of a game. The higher a team’s game script, the greater its propensity to run in order to bleed the clock and secure the win. By the same token, a team with a negative game script is more likely to pass in order to attempt a come-from-behind victory.

Which brings us to the 2019 Philadelphia Eagles. In weeks 1-4, as we’ve been repeatedly told, this team faced a 10 point deficit in every single game. Yet, despite having fallen behind early in four of their games, the Eagles, through week 5, have been one the run-heaviest teams in the league.

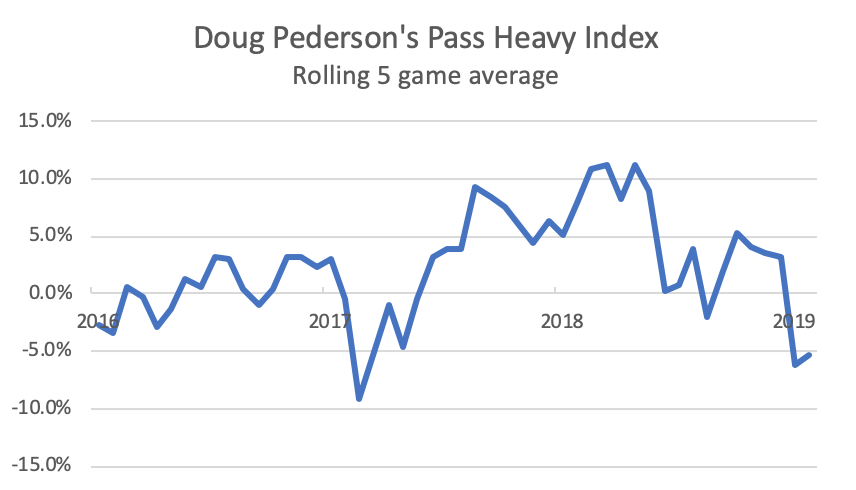

Recall the Pass Heavy Index, which computes the pass/run ratio relative to expectation given a team’s average game script:

The Eagles rank 23rd in the league, passing the ball 5.5% less frequently than would be expected, given their average game script (0.5). This is their lowest rank since Doug Pederson’s first year as a head coach, with a rookie quarterback. In the last two years, the Eagles have ranked 8th and 10th in terms of situation-adjusted pass heaviness.

Moreover, the first five games of 2019 have been the second most run-heavy five game stretch of Pederson’s tenure. The last time the Eagles were this run-heavy occurred during weeks 3 – 7 of the 2017 season, after Pederson endured considerable criticism from the likes of Frank and Joe from Manayunk following a week 2 loss vs Andy Reid’s Chiefs, when the Eagles passed on 75.4% of offensive plays, Pederson’s most pass-heavy game ever, given the game script (27.8% above expectation).

Does the recent run-heavy approach portend a shift in tactical emphasis, or could it be merely statistical noise? The plot below shows every Eagles regular season game under Pederson’s tenure, with 2019 games in red, labeled with opponents. The regression line shows the league-wide average pass-run ratio; the degree to which a data point is above or below the line reflects the “Pass Heavy Index” for that particular game (positive or negative).

Week 2 (at ATL) and 5 (NYJ) were pass-heavy, when adjusted for game script. Week 1 (TB) and 3 (DET) were more run-heavy than is typical for a Pederson offense. A significant proportion of 2019’s run-heavy tilt is due to the sublime Green Bay game at Lambeau when Doug passed the ball 24.2% less than what would have been expected, given the game script. This game was, by far, the most run-heavy of his head coaching career. There was reasoning behind this anomaly: Mike Pettine chose to keep his defensive personnel in dime and nickel versus the Eagles two tight end sets, allowing Zach Ertz and Dallas Goedert to run block against relatively light boxes. As Jason Kelce pithily explained to Sheil Kapadia, the objective in the game was to put the defense in a bind: “Everything’s just trying to get honest numbers out of them.”

Had Pettine loaded the box with base personnel, you can be sure that the Eagles would have been pass-heavy, particularly with Goedert and Ertz on the field. Removing the unusual circumstances of the Green Bay game, the Eagles -0.5% Pass Heavy Index would rank 17th in the league. Their current league rank, in terms of pass-run ratio, is at least partly an artifact of the game-theoretical nature of Doug Pederson’s offense, which is predicated on running versus light boxes and passing versus heavy boxes.

Per the NFL ScrapR box score app created by The Athletic’s Ben Baldwin, this tactic paid huge dividends. The Eagles at Green Bay had both a higher success rate and expected points added (EPA) per play in the running game, compared with the passing game.

Note that a more efficient run vs. pass game is unusual. In weeks 1 through 5 of 2019, as well as during Pederson’s prior tenure, the Eagles had a higher average success rate and EPA passing the ball versus running.

I will close with a prediction: in the following weeks, Doug will unleash Carson. As defensive coordinators begin to recognize that Jordan Howard is quietly efficient running behind Jeff Stoutland’s offensive line, they will increase the number of defenders in the box.

And Pederson and Wentz will take what the defense gives them.