The following is a guest post by @sunset_shazz.

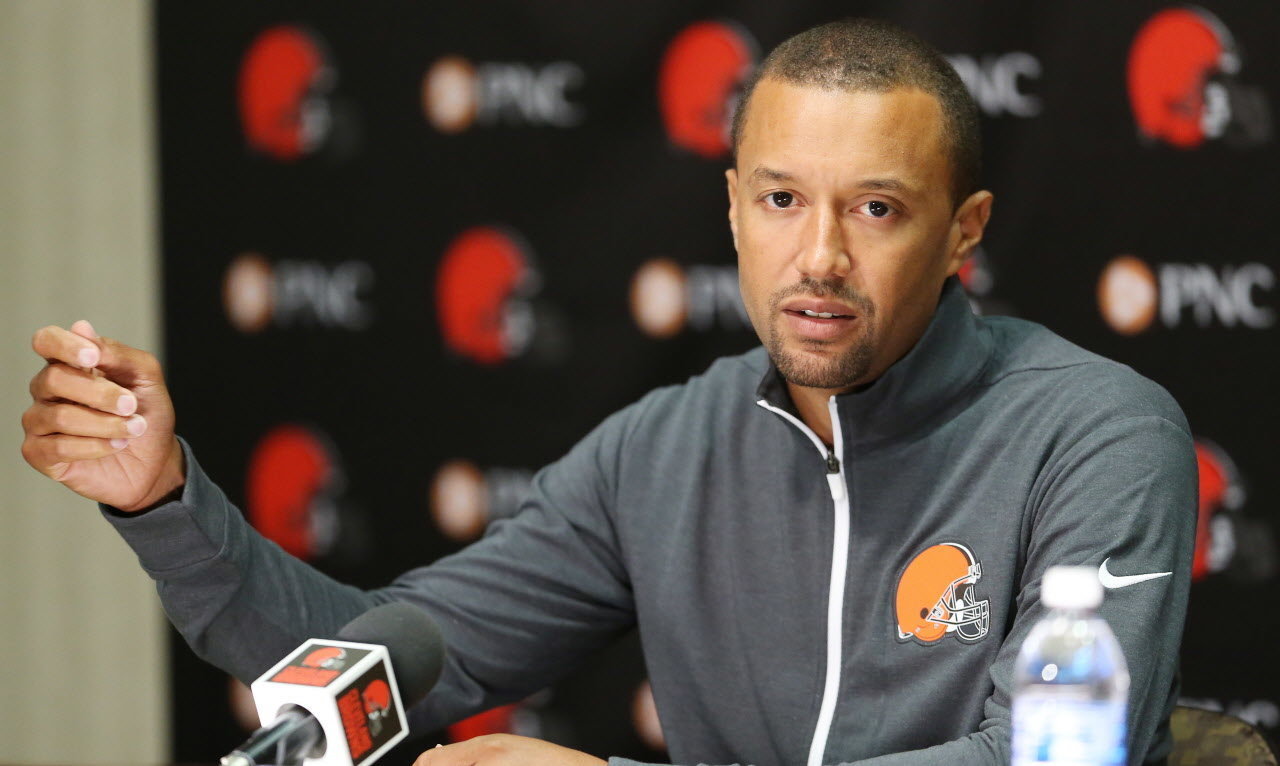

The news of Cleveland head of personnel Sashi Brown’s dismissal was met with uncharacteristic emotion by the customarily sober Aaron Schatz. Evidently, some quarters of the analytics community regard Brown, his colleague Paul DePodesta and the rest of the Browns front office team as one of their own. Brown’s strategy consisted of trading high draft picks for more (albeit lower ranked) picks. The opportunity cost of this strategy was to pass on both Deshaun Watson and Carson Wentz.

Talent evaluation is hard. You will be wrong more often than you will be right. I won’t fault Brown for misevaluating quarterbacks, just as I don’t fault 32 teams for repeatedly passing on Tom Brady (even the Patriots passed six times before using their 7th highest pick on him). There is data that suggests the market for talent evaluation is efficient and that no team has a sustainable edge.

But it doesn’t follow that just because you aren’t able to out-evaluate your peers, you should always trade down. Higher draft picks have higher success rates. The idea that lower picks might be undervalued dates from a classic 2005 paper by Cade Massey and newly-minted Nobel Laureate Richard Thaler. Massey-Thaler observed that NFL teams were overvaluing high picks relative to “the surplus value of drafted players, that is the value they provide to the teams less the compensation they are paid.” (Emphasis in the original.)

Two things have changed since 2005. First, the 2011 Collective Bargaining Agreement repriced the rookie wage scale, increasing the “surplus value” of higher picks relative to lower picks. [1] Secondly, the market learned and absorbed the Massey-Thaler result. We know from other domains that market inefficiencies almost always disappear as soon as they are found. Sashi Brown’s claim that talent markets are efficient – yet the market for picks is systematically inefficient – is an extraordinary claim, which demands extraordinary evidence. More likely, the market has moved from partial to general equilibrium. Football has no farm system; the strategy of hoarding picks is constrained by the 63-man roster and practice squad. Successful teams with quietly robust analytics departments (e.g. the Eagles and Patriots) trade both up and down, depending on the situation; constrained optimization is complicated. Moreover, as Brian argued in 2011, in order to fill the most critical position on an NFL team, the data shows you need to pick early.

But the real reason that Jimmy Haslam absolutely had to fire Sashi Brown is simple: his staff failed to execute a trade which was negotiated in good faith. Whether it exists under a buttonwood tree in lower Manhattan or in a coffee house in eighteenth century London, all markets are governed by rules, traditions and norms. As an example, the market for trading picks, which often occurs while teams are on the draft clock, is governed by trust and verbal agreements (not legal documents).

As Joseph Henrich notes in his brilliant anthropological survey The Secret of Our Success, pro-social norms are enforced in small communities through punishment, such as ostracism. In any community of traders, walking away from a duly negotiated agreement is a flagrant violation, a taboo. I will never forget how at the beginning of my career the head of our firm reacted to a similar situation: “We will never do business with those scumbags again, and we will make sure everybody knows how they have behaved.”

Punishing norm violators is not irrational. A trust-based community of traders is a fragile equilibrium. Erosion of trust can cause permanent, deadweight losses; thus pro-social norm enforcement evolves over time, and is Pareto efficient.

If Haslam had not fired Brown, some or all of the other 31 teams would have punished the norm violator by refusing to trade with Cleveland. This is both individually rational (trading with a deadbeat counterparty is risky) and collectively rational (pro-social norms promote gains from trade). Brown’s reputation as a counterparty was permanently impaired, thus compromising his ability to discharge his duties, and leaving Haslam with no choice but to clean house.

[1] Brian Burke found continued persistence of a second day surplus value anomaly, though it’s still early in terms of data, and as he notes, the replication model is sensitive to key methodological assumptions. His results cover the player market, but not the draft pick market.