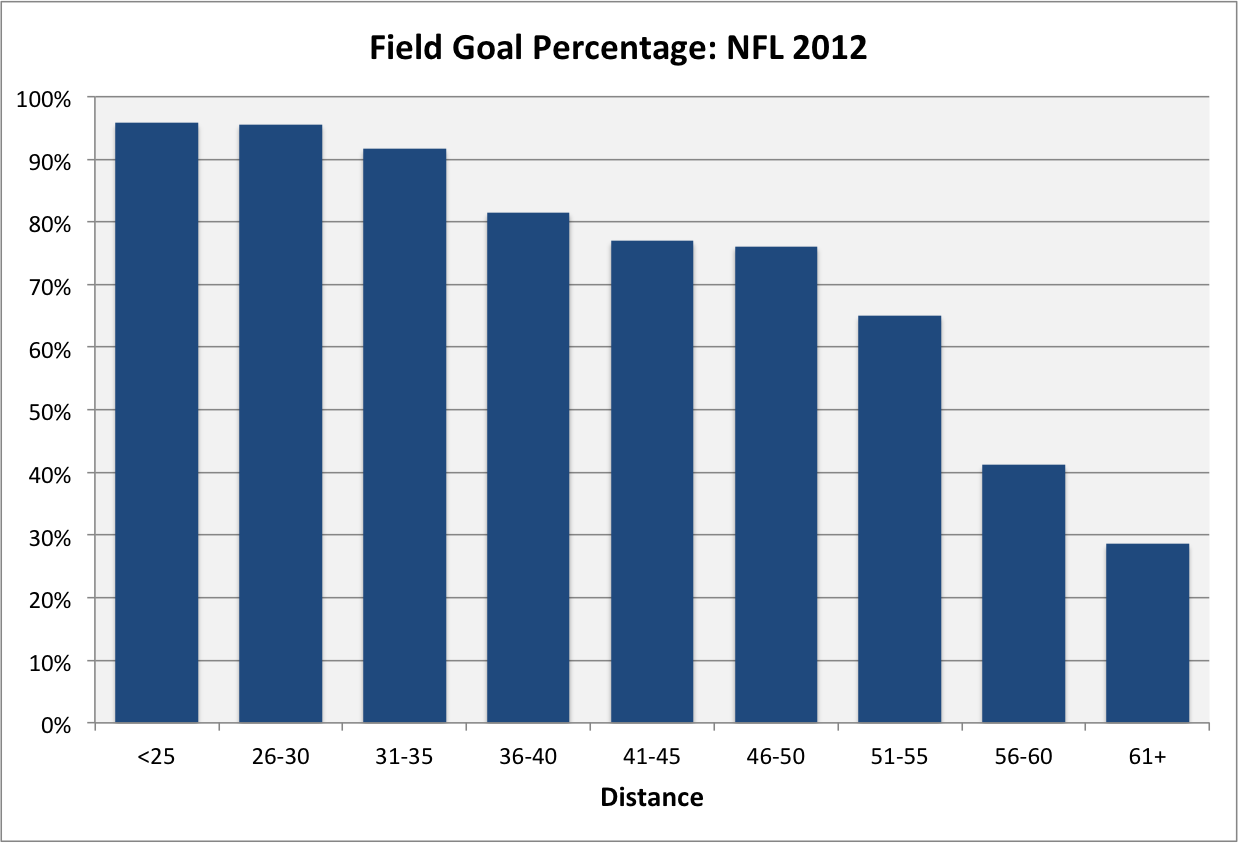

Everyone knows that NFL kickers are getting better. The numbers make this obvious. We saw an all-time high for field goal accuracy in 2013: over 86%. And that's despite many more long attempts. Field goal tries from over 50 yards have increased 57% in the last decade.

When ranking kickers, we have to take into account the new landscape. For an example, just look close to home. After his first three seasons, Alex Henery is tied for fourth all time in overall field goal accuracy among players with at least 80 attempts. But if you check out the top 20 on that list, 17 of them played in the last two years. This is like the late 1990s in baseball -- everyone's breaking records.

More to the point, we can't quote field goal accuracy without taking distance into account. As Jimmy Kempski noted, Henery doesn't look nearly as good when you compare him to his peers. Among full time kickers since 2011, Henery is tied for the fewest attempts over 50 yards (5). He also has the shortest "long field goal" (51). If everyone else is taking longer attempts and making them, Henery's value is significantly lower than his overall accuracy would suggest.

Last offseason, I took a deep dive into Henery's value, comparing him to other kickers in 2012. By generating an estimated value for every kick, we could plot how much each kicker actually contributed to his team as compared to the league standard. The results put Henery just a hair above average, with the noted caveat of having not a single make over 50 yards.

This year I wanted to go deeper. To start, I pulled all 2013 field goal attempts and plotted them out. While upgrading from last year's 5-yard buckets required a little smoothing, the granular data this year should be more exact:

Cool, right? As you can see, kicks from in close are automatic and everything up to about 32 yards out is a 90% success rate or higher. But perhaps even more impressive, kickers in 2013 maintained over 80% accuracy up to 45 yards out -- and 70% all the way to 55 yard attempts. The data gets meager from there, but the graph is proof of how great NFL kickers have become.

Anyway, with this data, it becomes fairly easy to generate an estimated point value for every field goal attempt. For example, a 35 yard try is worth 2.63 points while a 50 yarder is worth 2.1 points. If a kicker makes a kick from that distance, he adds points to his team above the expected value. Missing, he loses his team the expected points. (The only major caveat here is weather conditions. Certainly a field goal into strong wind would have a lower expected value than one in a dome.)

This year, we'll also add kickoff analysis. I spent some time playing with large data sets of kickoffs and ultimately was disappointed by the many problems in the NFL's play by play data. So at least until Football Outsiders releases its always-awesome game charting this summer, I can't work with the type of granular data on field goals above. The next best thing is Pro Football Focus' kickoff stats. They track distance, touchbacks, and average yard line start. I adjusted that data to eliminate the effect of onside kicks, but there are other variables (including weather) which still exist outside the scope of the investigation.

For kickoffs, the goal is to reach a similar expected value score. With help from Derek Sarley, we calculated a quick and dirty correlation between touchbacks and starting drive position of .67, suggesting that kickers have about two-thirds of the responsibility on kickoffs. Using that, we can multiply each kicker's total drive start yardage difference from the league average by .67, then by the approximately 0.06 expected points each extra yard is worth. Again, it's not a perfect score, but it will give us a good estimate.

Got all that? Click on the table below to enlarge the full results:

Hopefully the table isn't too confusing. Let's break it down. The left hand side is kickoff data, and you can see adjusted kickoff distance and drive start. From there you can calculate points generated in relation to the average kicker (KICKOFF PTS). On the right side are field goals, first the basic data then the estimated values based on the calculations above, leading to the FG PTS above or below average. Finally, TOTAL PTS combines the two scores and ranks all kickers (including those who only kickoff or attempt field goals).

The best kickers of 2013 did well on both metrics. Dan Bailey of the Cowboys, for example, helped force opponents to start their drives 1.9 yards further back than average. Over the course of the season, that was worth just over a touchdown in field position. On field goals, he made over 93% of his attempts, when the average kicker would have only made 84.5%. That was another 8 points he generated for Dallas, bringing Bailey's total points over average to a league-leading 15.1. If we can translate that using Brian Burke's data at Advanced NFL Stats, Bailey was worth about as much in expected points added as the 25th-ranked quarterback.

On the other end of the spectrum, Henery ranked third-worst in the NFL last year. He lost the Eagles approximately 10.8 points, split about equally between kickoffs and field goals. Henery was near the bottom of the pack in kickoff distance and average drive start, losing 1.6 yards per kickoff. Meanwhile, his 80% field goal accuracy should have been better, given he took mostly shorter kicks. The league average accuracy for his attempts would have been 85.8%.

Though Henery has some ardent supporters, it's tough to find any silver lining for him in these numbers. Only two kickers in this sample had worse results: a historically-bad rookie and a veteran who was fired in December. Maybe Henery can improve this offseason and post a better effort in 2014. But I wouldn't count on it. At the very least, the Eagles must bring in competition for what is clearly one of their weakest positions.