Every NFL coach or coordinator who’s ever taken a job has emphasized “fundamentals.” On the defensive side, you have to play aggressively, be physical, make sound tackles. Yet, according to his statements over the last few days, that’s essentially new Eagles defensive coordinator Juan Castillo’s entire plan: “be fundamentally sound.”

Certainly we wouldn’t expect Castillo to lay out his whole defensive philosophy in his first press conference. But two years ago, when Sean McDermott replaced the late Jim Johnson, we did get an immediate sense that McDermott had a clear idea of his Xs and Os. On his first day, the former coordinator said:

“There is one thing I know, and that is that this system, it works. Jim has spent a considerable amount of time in his coaching career researching and finding things that work and finding things that didn’t work, quite frankly, and I’m going to respect that and we’re going to build on that. From there we’ll add wrinkles.”

McDermott obviously had a plan to take the blitz concepts and continue to tinker with them. When asked basically the same question, Castillo replied:

“First of all, what we’re going to do is be fast and physical, and we’re going to be fundamentally sound. We have good players here. This is the NFL, you change, you upgrade, players get hurt, but that’s what we’re going to do.”

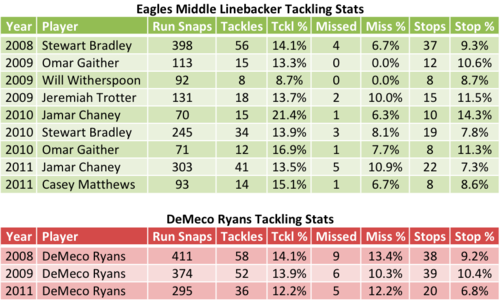

Since Castillo has defended those talking points recently on the radio as being the key to his success as an offensive line coach, we can assume for now that it’s essentially his philosophy. At this point you might say: what’s wrong with emphasizing fundamentals? McDermott was a scheme guy, and that didn’t turn out particularly well. Maybe if we get a coordinator who puts a priority on tackling and other basics, that will be enough to put the defense over the top.

There are two problems with this line of thinking. First, teaching fundamentals alone won’t set you apart. Doesn’t every coach teach fundamentals? You don’t think Super Bowl defensive coordinators Dick LeBeau and Dom Capers put their teams through endless tackling and other drills in practice? Of course they do. But they also have talented players and put them in good positions to succeed through complex coverage and pressure schemes.

The second problem is that this theory is based on an underlying bias we have toward valuing what we can see. The biggest example of this is missed tackles. Every fan and their grandmother can see when Asante Samuel whiffs on a running back coming right at him or Juqua Parker comes up empty on an easy sack. At the end of the game, we tend to blame these mistakes for the defense’s failure and make comments like, “they need to go back to fundamentals.”

Yet missed tackles are only one tiny part of a horrible defensive play or series. Think about everything else that went into that: bad play calling, inadequate scheme, unbalanced one-on-one match ups, lack of player talent, poor decision-making and play recognition, failure to get off blocks or take a correct angle on the ball-carrier, even luck. All these factors matter much more than a given missed tackle, but we only remember Nate Allen diving for the running back’s ankles and coming up empty.

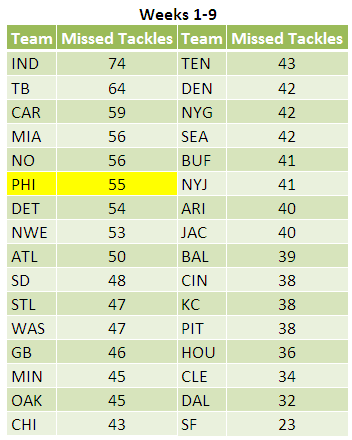

Statistically, though, fewer missed tackles has zero correlation to a better defense. There’s no connection between missed tackles and opponent yards, points, or touchdowns per drive. Why? Because while missed tackles stick out in our minds, there aren’t enough to radically affect the success of defense. The difference between the very best and very worst tackling teams in the NFL in 2010 is about three missed tackles per game. Insignificant.

That’s why it’s worrisome to hear that Castillo’s only talking point is that the defense in 2011 is going to “be fundamentally sound.” That might work in the offensive line trenches, but in the grand chess match of offensive vs. defensive coordinators, fundamentals just don’t make as big of a difference.

Originally published at NBC Philadelphia. Photo from Getty.